Forests are an extremely important part of Myanmar’s natural resources. However, competing economic interests have resulted in the country having one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world. 1 The state owns all land and forest in Myanmar 2, but external business interests are increasing. Local communities and ethnic minorities have traditional and legal interests as well. 3

Wood for firing brick-making ovens for the economic interest. Photo by James Anderson, World Resources Institute via Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Forest management has been on the state agenda since colonial times. 4 However, since at least the 1970s there has been a greater understanding of the role of conflict, land concessions, and illegal and unsustainable timber harvesting in deforestation. 5 While the state has developed policies and legislation on forest conservation, including community forestry, external actors have increasingly focused on the role of the state itself in perpetuating unsustainable and illegal logging practices. External mechanisms for changing the sector have typically focused on economic sanctions, particularly to limit the role of forestry in funding the military. 6, 7 However, critics suggest that this may actually increase deforestation and illegal logging in Myanmar. 8

Rubber and palm oil plantations or the mining sector impact at conflict areas which have displaced villages like Kan Par Ni in Myanmar. Photo by NFNPA via Flickr, Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Forest Protection Legal and Policy Framework

Myanmar’s forests are governed by many different policies, laws, and regulations. The full list can be viewed on the Forest Policy and Administration page.

Role of government

Ministerial meeting in support of Myanmar National REDD+ Strategies Development at Nay Pyi Taw. Photo by REDD Plus Myanmar via Flickr, Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

The Forest Department under the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation (MONREC) is the main government institution responsible for forestry management. However, other departments under MONREC are also responsible for forests, as is the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation. A recent statement 9 by the military-appointed minister of MONREC indicates forest management, including timber exportation, is now under the control of the military junta. More can be read about government administration on the Forest Policy and Administration page.

A 30-year National Forestry Master Plan (NFMP) (2001/2–2030/1), developed by the Forest Department, guides the development of 10-year forest management plans. Using so-called ‘wasteland’, much of which is likely to be land under customary tenure, 10 the aim is to increase Reserved Forest (RF) and Protected Public Forest (PPF) by roughly 4 million hectares. 11 More can be read about the forest classification system on the Forest Policy and Administration page.

The 2015 civilian government endorsed the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 12 Participation in climate change-related REDD+ and making Nationally Determined Contributions as a party to the UNFCCC were also part of the strategy. Forests are a key aspect of these climate change programs. The government also endorsed the Myanmar Climate Change Policy (2019), National Environmental Policy (2019), and the Myanmar Climate Change Strategy (2018-2030). 13

Role of Non-Government Organizations

Prior to the 2021 military coup, more than 45 NGOs and civil society organizations (CSOs) were working on environmental conservation in Myanmar. 14 Forest-specific organizations include the Center for People and Forests (RECOFTC), Myanmar Environment Rehabilitation-conservation Network (MERN), Karen Environmental and Social Action Network (KESAN), and Kachin Development Networking Group (KDNG). RECOFTC and MERN have also collaborated with the government to promote forest protection and reforestation.

World Environment Day cerebration at the Nay Pyi Taw, Yangon, in 2017. Photo by Photo by REDD Plus Myanmar via Flickr, Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

However, since the military regime seized control, many NGOs have been unable to progress. For example, forest monitors working with the Environmental Investigation Agency, an organization investigating timber trading, have been unable to collect data as most forest partners have needed to relocate or are unable to work. Another organization promoting sustainable forest management through certification, PEFC, is now unable to provide certification due to conflicts within the sector’s certification standards. 15

Role of local communities

Local communities of ethnic minorities16 play a fundamental role in caring for forests. 70% of Myanmar’s population live in rural areas, relying on forests for basic needs. 17 Most rural villages are made up of ethnic minorities or Indigenous Peoples, who also have spiritual and familial ties to forests. These roots of customary tenure, along with customary practices and traditional knowledge, guide their approach to forest governance.

Outreach meetings between MONREC and CF for the Agroforest project at the Kyit Some Swe village Photo by FLEGT Myanmar via Flickr, Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Customary land tenure is not yet legally recognized in Myanmar. However, the National Land Use Policy (2016) includes principles on managing and recognizing customary tenure, including suggested protection under the draft Land Law. 18 19 The government also allows for limited expressions of customary land tenure in practice. 20

Local communities continue to take care of their traditional sacred forests. In some cases, this has led to the creation of protected forest areas that do not fall under the national legal framework. 21 This has especially been the case in non-state administered areas (NSAs), with a well-known example being Kaw, or the Salween Peace Park. The park was established by a group of Karen on their customary land to protect their cultural heritage and autonomy.

Karen Community forest inside KNU controlled Area. Photo by Photo by NFNPA via Flickr, Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

NSA forest actors need to register with both the NSA and national authorities. 22 However, it is unclear from which authority a NSA forest actor should apply for a forest certificate. 23 This means each NSA forest is recognized differently by the national government. Kaw has a long-term lease with the national government but has received its internationally recognized certification from the Karen Forest Department. 24 Other forests cared for by communities in NSAs in Karenni, Kachin, Karen State, 25 and Tanintharyi Region26 have also applied their customary laws, governance systems, knowledge, and practices toward forest management. 27 In addition to Kaw, the Thawthi Taw-Oo Indigenous Park was established in 2019. 28

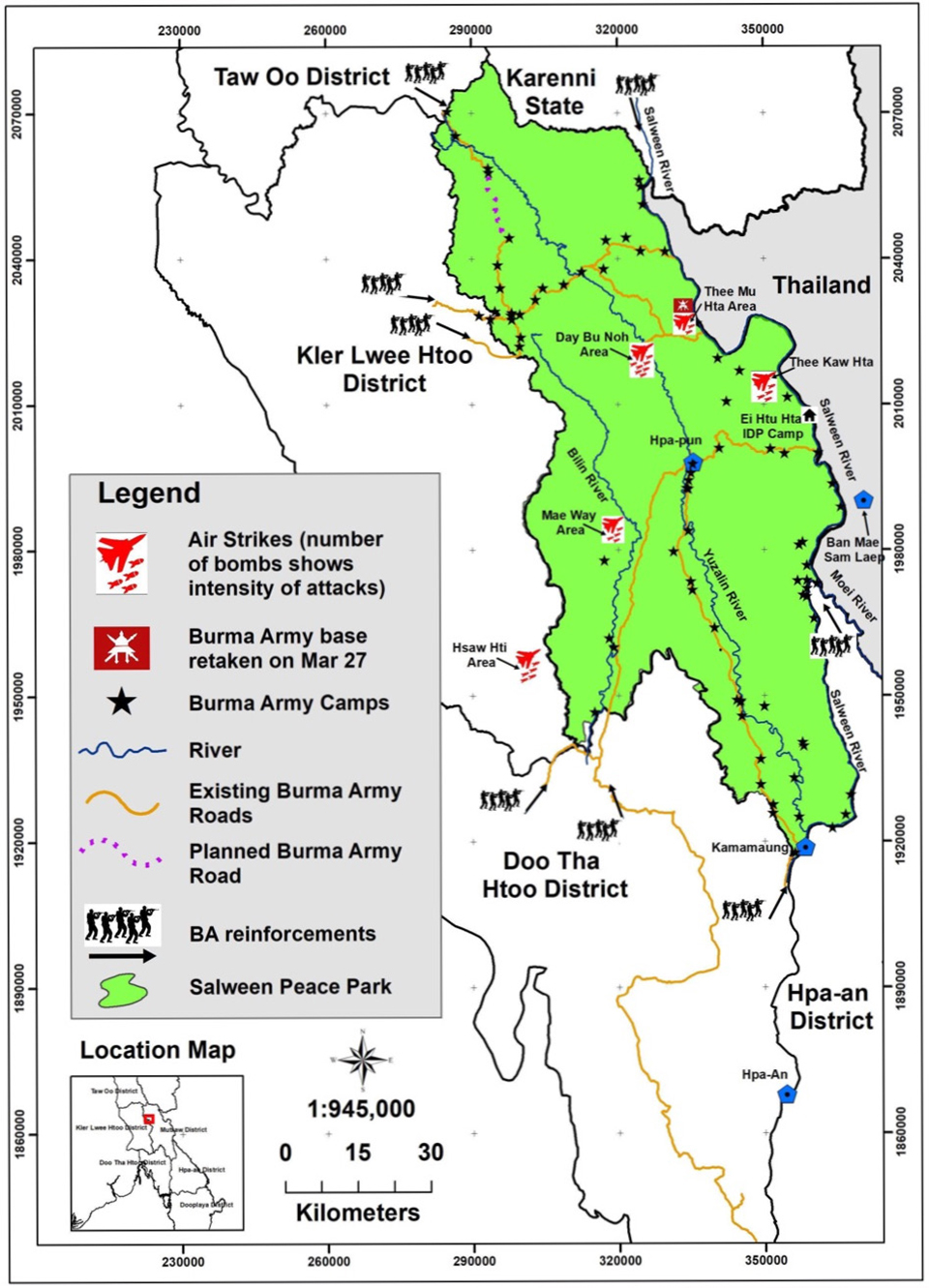

Community-protected forests in NSAs often have competing interests. 29 For instance, the 2019 Community Forest Instructions (CFI) limits ethnic governance in forest management. 30 In addition, various laws relevant to forests are at odds with each other and with community-driven forest protection. For example, the Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Land Management Law, discourages shifting cultivation, a usual technique of ethnic communities. Ultimately, all forests, including ones in NSAs, remain under the Myanmar constitution. These areas are called “mixed control”. See map 1.

Community Forestry

The national government’s policy to support sustainable forestry includes Community Forestry (CF). While CF can also refer to locally-driven forest conservation by ethnic minority communities acting in accordance with their customary tenure rights and responsibilities, this piece uses the words Community Forestry (CF) and Community Forest to refer only to forests involving local communities in governance structures developed under the national framework.

Teak’s plantation yard in the community forest. Photo by Photo by FLEGT Myanmar via Flickr, Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

The national CF framework is guided by the Forestry Master Plan (2001-2031), Forest Law (2018), and the Conservation of Biodiversity and Protected Areas Law (2018) and implemented through the Community Forest Instructions (CFIs) 1995, 2016, and 2019. 31Unlike community-driven forest conservation, nationally-driven Community Forests require applicants to register with the national government for a certificate. Once a CF certificate is received, registered users can develop Community Forestry Enterprises (CFEs) and Community Forest User Groups (CFUGs). 32 Through these, registered communities may sell forest products while supporting the regeneration of degraded forests for 30-year periods that can be extended. 33 State-recognized CF has more economic opportunities than NSA forests, as the state provides enterprise training and financial support to CFEs and CFUGs, and CFEs can sell teak and ironwood legally. 34 CF can be found in areas with long-term forest degradation, 35 including Shan, Mandalay, Magway, Sagain, Tanintharyi, Kachin, Mandalay, Rakhine and Ayeyarwady. 920,000 ha of state-supported Community Forests is supposed to be established by 2030,36 but only 248,967 ha of Community Forests had been established by 2019. 37

Gender in forestry

Women’s roles in forestry are diverse across Myanmar due to the diversity of cultural traditions and changes in the way people make a living as commercialization increases. In general, rural women tend to engage with forests for domestic needs, such as gathering firewood, vegetables, and food. 38 Women in Myanmar also hold knowledge on forest protection, developed by growing seeds and plants and caring for native species. 39 In contrast, men interact with forests but are more likely to focus on extraction than conservation. 40 In some communities, like the Karen, women may be the only holders of specialized knowledge of certain plants and herbs. 41 In addition, in some forests, women play a more central role in forest management, such as at Kaw. 42 Yet, overall, males mostly dominate in decision-making in community-driven forests. 43

Women participation at the land tenure training at the MinHla Township, Bago Region. Photo by USAID via Flickr, Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Like women elsewhere, ethnic minority women encounter additional barriers to participation in forest governance. They are typically required to do domestic work alongside their farming and livelihood activities, restricting the amount of time they can devote to forest management discussions. 44 Cultural norms requiring women to have an escort impact the mobility of women as well, and remote forest areas – considered unsafe for women and girls – can require an overnight stay to access. 45 Further, women are told to stay at home to avoid the risk of sexual violence in mixed control areas where some non-state community forests are located. 46 Furthermore, ethnic women live in remote rural areas, which have particularly limited access to education. This has weakened their ability to participate in both forest governance and implementation activities. 47

Rural women gathering vegetables and food from the forest. Photo by FLEGT Myanmar via Flickr, Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Since the military coup in February 2021, forest areas have also become dangerous for people to enter. Communities, especially women, are less mobile due to increased safety concerns, further limiting their ability to care for their forests and to access resources. 48 49

Women in State-controlled Community Forestry

Like in NSA forests, women are under-represented in CF. Formal education is a key criterion for CF governance structures, but since rural women are less able to access education opportunities, they are also less likely to be literate in Burmese. Thus, they are unable to meet the legally prescribed education requirements for participation in spite of having a strong knowledge of forestry. Opportunities for input are male-dominated, which can be intimidating and may feel unsafe for women to discuss the issues. Further, with an unquestioned requirement to do domestic work, combined with low awareness of rights, and a male-dominated culture forbidding women’s participation, 50 gender inclusiveness in state-governed CF has been very limited.

An ethnic Pa Oh Woman carrying her baby in the farm. Photo by Paul Arps, via Flickr, Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

While the government aims to increase women’s participation through community forest management plans, 51 the guidance on gender in benefit sharing and forest resource management remains unclear. 52

Map 1: Map of airstrikes on 27 and 28 March 2021 in the Salween Peace Park and nearby villages in northern Karen State, Burma/Myanmar. Source: Salween Peace Park

References

- 1. FAO. 2015. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015: how are the world’s forests changing?. Accessed September, 2021.

- 2. Article 3 of Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution

- 3. ETTF. 2020. Myanmar industry profile. Accessed November, 2021.

- 4. Open Development Myanmar. Forest and forestry. Accessed November, 2021.

- 5. Ibid.

- 6. Mongabay. 2021. Myanmar’s troubled forestry sector seeks global endorsement after coup. Accessed November 2021.

- 7. Open Development Myanmar. 2020. Forests and forestry. Accessed November, 2021.

- 8. Michael Taylor. 2021. Myanmar’s Forests Are at Risk After Military Coup and Economic Sanctions. Accessed September, 2021.

- 9. Myanmar Forest Products and Timber Merchants Association. 2021. Issuing a statement for legal and official export of teak from Myanmar to EU countries. Accessed November, 2021.

- 10. MONREC & World Bank. 2019. Myanmar Country Environmental Analysis. Accessed September, 2021.

- 11. MONREC, & UN-REDD/Myanmar. 2017. Drivers of deforestation and forest degradation in Myanmar. Accessed November, 2021.

- 12. Open Development Myanmar. 2018. Sustainable Development Goals. Accessed September, 2021.

- 13. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2019. Myanmar Climate Change Strategy (2018 – 2030). Accessed November, 2021.

- 14. MCRB’s. 2018. Local and international environmental organisations working on biodiversity conservation. Accessed September, 2021.

- 15. PEFC. 2021. Statement on the current situation in Myanmar. Accessed November, 2021.

- 16. Including those not recognized by law as “national races”

- 17. FAO. 2020. Forests for people: Myanmar puts its REDD+ Safeguard Information System into practice. Accessed September, 2021.

- 18. FAO and MRLG. 2019. Challenges and opportunities of recognizing and protecting customary tenure systems in Myanmar. Accessed October, 2021.

- 19. IWGIA. 2020. Strong Roots. Accessed September, 2021.

- 20. IWGIA. 2020. Strong Roots. Accessed September, 2021.

- 21. FAO and MRLG. 2019. Challenges and opportunities of recognizing and protecting customary tenure systems in Myanmar. Accessed October, 2021.

- 22. The World Bank. 2019. Myanmar Country Environmental Analysis: Assessing the opportunities for scaling up community forestry and enterprises in Myanmar. Accessed October, 2021.

- 23. Ibid.

- 24. Scott Ezell. 2019. The Importance of Saving Biodiversity in Karen State in 2 Interviews. Accessed November, 2021.

- 25. KESAN. Salween Peace Park Initiative. Accessed September, 2021.

- 26. CAT. 2020. Tanawthari Landscape of Life. Accessed September, 2021.

- 27. MONREC & World Bank. 2019. Myanmar Country Environmental Analysis: Forest Resources Sector Report. Accessed September, 2021.

- 28. KESAN. 2021. Thawthi Taw-Oo Indigenous Park (TTIP). Accessed October, 2021.

- 29. The World Bank. 2019. Myanmar Country Environmental Analysis. Accessed October, 2021.

- 30. Ibid.

- 31. MONREC. 2019. Community Forestry Instructions. Accessed September 2021.

- 32. MONREC & World Bank. 2019. Myanmar Country Environmental Analysis: Forest Resources Sector Report. Accessed September, 2021.

- 33. FAO and MRLG. 2019. Challenges and opportunities of recognizing and protecting customary tenure systems in Myanmar. Accessed October, 2021.

- 34. MONREC & World Bank. 2019. Myanmar Country Environmental Analysis: Forest Resources Sector Report. Accessed September, 2021.

- 35. Ms.Thin Thin Moe. 2019. Community Forestry and Rural Livelihoods in Myanmar. Accessed September, 2021.

- 36. Tian Lin & Maung Maung Than. 2019. Myanmar must improve its community forestry plan to fight climate change. Accessed September, 2021.

- 37. MONREC & World Bank. 2019. Myanmar Country Environmental Analysis: Forest Resources Sector Report. Accessed September, 2021.

- 38. Ibid.

- 39. IWGIA. 2020. Strong Roots. Accessed September, 2021.

- 40. Aye Chan Myae. Empowering women in forest governance contributes to forest conservation and poverty reduction. Accessed October, 2021.

- 41. IWGIA. 2020. Strong Roots. Accessed September, 2021.

- 42. International River. 2020. Peace on the Salween. Accessed September 2021.

- 43. International Alert. 2020. Rooting out inequalities. Accessed October, 2021.

- 44. Ibid.

- 45. Ibid.

- 46. Ibid.

- 47. Ibid.

- 48. Ibid.

- 49. Frontier Myanmar. 2021. The fate of our forests is in the balance. Accessed September, 2021.

- 50. Aye Chan Myae. Empowering women in forest governance contributes to forest conservation and poverty reduction. Accessed October, 2021.

- 51. MONREC & World Bank. 2019. Myanmar Country Environmental Analysis: Forest Resources Sector Report. Accessed September, 2021.

- 52. Aye Chan Myae. Empowering women in forest governance contributes to forest conservation and poverty reduction. Accessed October, 2021.